Hinduism, the world’s most eclectic religion, does not have a single founder or God and the only one which does not have a holy book as the one and only one scriptural authority. The word “Hinduism” was coined by European travellers and traders in the 16th century.

Although around 80 percent of India’s population calls itself Hindu, Hinduism is not a religion in the same way as Christianity or Islam. The latter two denote a precise faith in Jesus, the Son of God and in Mohammed, the Prophet of Allah. In Hinduism, there is no divine authority, no absolutes in terms of good, evil and sin, no canonical laws or commandments, no final retribution or reward, no congregational worship, no day of rest nor specific day set aside for God.

One may regard the Rig Veda as one’s personal bible, or one may turn to the Upanishads, or the Bhagvad Gita; or one may dispense with all the sacred texts and still claim to be a good Hindu. One may worship Vishnu or Shiva or some other gods or goddesses; or one may not worship any deity and meditate on the Supreme Spirit dwelling within one’s own heart.

Even though belief or faith are a matter of personal conviction, temples, rituals and priests exist as the Hindu goes to the temple whenever he wishes to offer prayer, make an offering in fulfillment of a vow, listen to a discourse or just to meet friends. Temples, ostensibly built to glorify the gods, were also at the hub of affairs at a time when modern day meeting places did not exist. The silence of “piety” is in fact quite alien to a Hindu temple where the continuous cacophony of music, chanting, mothers calling for their children, flower sellers and incense vendors announcing their wares predominates. In fact the Hindus visit their gods rather like they visit friends! Priests have officiate at births, deaths, marriages and special ritual ceremonies for they alone are versed in the religious texts. However, most religious ceremonies are family affairs and take place at home. The Hindus are not idol worshippers, but a profusion of god-figures proliferate temple walls.

Lead me from the unreal to the real.

Lead me from the darkness to light.

Lead me from death to immortality.

– an invocation from the Upanishads

The word ‘Hinduism’ itself is a misnomer. In the old days – I mean really old – perhaps more than 7000 years ago, this religion was called Sanatana Dharma – or the way of the Universe. The foreigners who came here, found Sanatana Dharma too difficult to pronounce. The easier way to call the natives was after the Indus Valley Civilization.

Indus itself is another corruption of the word Sindhu – the river – which flows from the Himalayas to the west – now in Pakistan. Explorers found this river easily on the land route from Europe and named the people (derogatorily called natives) as Hindus.

Frankly, the Islamic and Christian fundamentalists did not understand how a religion could exist for thousands of years without going to war on the issue.

Of course, Hindu kings fought Hindu kings – but that was politics. But there was no jehad or crusade. And in Hinduism – there is no concept of evil or Devil. Every being created by the preceptor Brahma is good and sometimes, out of circumstances beyond his or her control, adopt bad ways. But even the baddies pray to God – there are several of them to get unlimited powers. After attaining them, the ambitious beings who think that they can excel the gods. But in the end, they are defeated and lo! they are rid of their curses and become Gods again.

There is, however, a term for hell in Hindu mythology – Naraka. But even that region is governed by Dharma Raja – the king of righteousness who himself is a God. And any soul that has to suffer in hell, is there only for a temporary phase. The final destination is always heaven. If a soul has done enough good deeds on earth, rightaway, it goes to heaven – in layman’s words for the Sanskrit term is Swarga or Paradise. Should sins outnumber the merits of a soul, the temporary destination, according to Puranas – or ancient texts, is Naraka. But the journey doesn’t end there. According to the theory of Karma a human being is born as many times on this earth as is necessary to shed his or her bad Karma and finally attains Mukti – salvation.

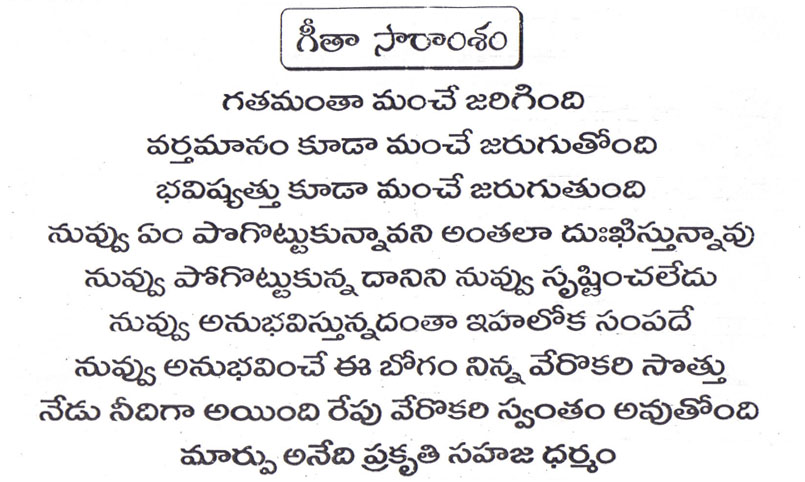

This philosophy is enumerated clearly in the Bhagavad Gita – an intrinsic part of Mahabharata – the greatest epic written. The tenth incarnation of Lord Vishnu – who is in charge of safeguarding the lives of all those on earth and above, – in human form – Lord Krishna – is quoted extensively by Sage Vyasa who wrote the epic.

The Mahabharata is rendered in lucid style in both English and Tamil by C. Rajagopalachari – an enlightened soul of the 20th century. The books are available in Giri Trading Agency in Chennai and Mumbai. The book is in paperback form – and has already had a print run of over a million copies and still is a bestseller. In these books the Bhagvadgita is explained in great detail in a language that can be easily comprehended by the common man. For those who want to delve deeper – try Bhagvadgita written by Swami Chidbhavananda or Chinmanayanda. Swami Vivekananda has also elaborately written on all the yogas described by Lord Krishna in Gita. All these are available in Giri Trading Agency.

For those who do not know the long and the short of it in Mahabharata -it is the before and after of an epic war between the Pandavas (or children who took Pandu’s name though born out of the gods), and Kauravas – the evil ones try to usurp other’s property by foul means. In the end there is a major war, which leaves millions dead, but Pandavas emerge victorious.

Coming back to the Bhagvadgita, just to give an idea of the manifestation of the Lord – I recall these words translated by me from the Hindi television version of the epic. Krishna says: Amongst stars I am the Sun, amongst planets I am earth, amongst Gods, I am Vishnu, amongst the mountains I am the Meru, amongst Pandavas, I am Arjuna (kindly remember, this is during a discourse being given to Arjuna himself) and amongst Kauravas – I am Duiryodhana. The last part – Duryodhana should be interesting for all those who should get enlightened about the non existence of the concept of evil. Duryodhana was the usurper and committed various sins. But he was the best amongst the evil doers. God says that he is present even in Duryodhana because, he is omni potent and omnipresent. And in the end of Mahabharata, when was Duryodhana was defeated and killed in war – he went straight to heaven – paradise, so the Mahabharata says.

This probably would have given you an idea about the secular nature of Hinduism.

Who is a Hindu?

“Acceptance of the Vedas with reverence; recognition of the fact that the means or ways to salvation are diverse; and the realization of the truth that the number of gods to be worshiped is large, that indeed is the distinguishing feature of the Hindu religion.” B.G. Tilak’s definition of what makes one a basic Hindu, as quoted by India’s Supreme Court. On July 2, 1995, the Court referred to it as an “adequate and satisfactory formula.”

The Ramayana is considered the first ornate poem and is attributed to the sage Valmiki. Its present form has seven books and about 24,000 slokas or verses, though the last book is an epilog written later as was probably most of the first book. Treatment of Rama as an immortal god, an incarnation of Vishnu, is mostly found in these later books. Nevertheless the entire poem is heroic, and Rama along with his wife Sita are superhuman in their virtue and perfection. For Indian culture they represent models of ideal behavior and attitudes.

The time period of the Ramayana has been estimated as between the twelfth and tenth centuries BC when the Kosalas and Videhas ruled northern India. A legend about the author Valmiki tells how he was a robber chief, who once waylaid two ascetics; they offered him spiritual wisdom in place of gold and silver which they did not have. Won over by their ideas, Valmiki became a devotee of Rama, the seventh incarnation of Vishnu, and after meditating much on Rama and his virtues he was given a vision of his entire life.

Valmiki asked Narada, who was most heroic and virtuous, and was told of Rama as the most self-controlled, valiant and illustrious, the Lord of all. Narada declared that he is equal to Brahma, a protector of the people, supporter of the universe, subduer of those who violate the moral code, the inspirer of virtue in others, and one who grants grace to his devotees. Having told Valmiki the story of Rama, Narada asked permission to leave and ascended to heaven. Then the poet Valmiki put the story into verse based on the details he perceived in his meditative vision.

The story begins in Ayodhya, where Rama’s father ruled as king in the tradition of Manu. The community was prosperous and happy, and the Brahmins understood the six systems of philosophy. Dasaratha’s ministers were guided by the moral code and reason; it was a golden age, an age of truth (satya-yuga). According to the first book, Vishnu decided to incarnate in the sons of Dasaratha in order to destroy the cruel leader of the demons, Ravana, who through austerity had gained the boon of being invulnerable to all but man.

Dasaratha had more than one wife, and each of his four sons was born to a different mother, but clearly the greatest was the oldest Rama, followed by Lakshmana, Bharata, and Shatrughna. Taught by the sage Vishvamitra, Rama slays the demon Takaka and is given celestial weapons. Sita, who was mysteriously born in the furrow of a field, which is what her name means, was to be given in marriage to the one who could bend a certain bow. When Rama bent the bow, it broke in two; so Rama and Sita were married. Rama proves his valor and skill by stringing another bow and defeating Parasurama in combat. Sita communicated all her thoughts to Rama and could clearly read his mind, so dear were they to each other.

The second book begins by describing Rama’s many virtues. The elderly King Dasaratha decides to hand over the rule of his kingdom to his illustrious eldest son, Rama, but on the day before his installation, Queen Kaikeyi, the mother of Bharata, is persuaded by her hunchback servant Manthara to ask the king for the two boons he owes her for having saved his life. Her son Bharata must be made regent, and Rama must go into exile in the forest for fourteen years.

While the people of Ayodhya are celebrating the expected coronation of Rama, he goes to the palace only to be commanded into exile by the king. Everyone who loves Rama is stricken with grief, but Rama allows himself no sign of emotion and willingly submits to the royal will. Lakshmana protests and wants to fight for Rama’s rightful place, but Rama persuades him that they must obey their father out of duty and not use violence; what is right is more important than a mere kingdom. Rama also urges his mother, Kaushalya, to stay with her husband rather than follow him into the forest.

Sita, however, is able to convince Rama that it is her duty to be with her husband. Unable to persuade her to stay behind, Rama says he cannot abandon his wife. Sita gives away her possessions in preparation, and Rama is acclaimed by the people for his virtues of harmlessness, compassion, obedience, heroism, humility, and self-control. The king believes that he must have deprived countless beings of their offspring to have to suffer this separation from his beloved son.

Lakshmana accompanies Rama and Sita, and the emotional parting is ended by Rama’s ordering the chariot-driver to hurry away. They cross the Ganges River and enter the wild forest. Rama sends the chariot-driver back to the court to tell them he will live as an ascetic, and so Kaikeyi should not be suspicious but enjoy supreme authority in the name of her son Bharata. Rama’s small group is guided further into the forest by local leaders and sages.

Rama realizes that his mother must have done something in a former life to have her son taken away in this one, and Dasaratha tells how once while hunting he accidentally killed the son of two blind parents as he was getting water for them. Realizing the fruit of that action in his current sorrow, King Dasaratha soon dies of grief. Kaushalya reprimands Kaikeyi saying that one who is ambitious is unaware like one who eats unripe fruit.

The counselors decide that Bharata should be made king. He has been living in Rajagriha with his grandparents, but a dream reveals the death of his father. Returning to Ayodhya Bharata reproaches his mother Kaikeyi for her selfish plot to put him in Rama’s rightful place, and he suggests that she commit suicide. Bharata consoles Kaushalya, and the funeral ceremonies are held amid much sorrow. Shatrughna wants to punish the hunchback woman, Manthara, but Bharata persuades him that Rama would not approve of such killing or Bharata would have killed his own mother too.

Bharata decides to refuse the throne and offer it to Rama. Bharata crosses the Ganges and eventually finds Rama in the forest. When Lakshmana sees Bharata’s army approaching, he fears the worst and is ready to fight; but Rama explains he only would want the throne to protect his brothers and would never fight against them. He correctly perceives that Bharata is coming to offer him the throne. When the four brothers are reunited, Bharata and Shatrughna allow their tears to fall.

Rama asks Bharata if he is fulfilling his royal duties, but Bharata says that as the eldest Rama ought to be king. However, Rama declares that the royal word of their father must be their law, and therefore Bharata must rule for fourteen years while Rama is in exile. Bharata begs Rama to return to Ayodhya, but Rama steadfastly refuses. Rama explains that morality is the soul of government, and that is how the people are upheld. The essence of duty is truth, and therefore he must keep his word to his father. Rama renounces the so-called duty of the warrior which is violent, saying it is injustice under the name of justice and the practice of the cruel, depraved, and ambitious who do evil. He prefers to live in the forest free of sin in peace, enjoying pure roots, fruit, and flowers.

Bharata asks for the golden sandals of Rama and is given them as a symbol of Rama’s absent rule through Bharata. Celestial gifts are conferred on Sita as she declares her loyalty to her husband as her guru and master of her heart. She believes that obedience to one’s Lord is the crowning discipline for a noble woman

In the third book Sita is carried off by the demon Viradha, but Rama and his brother get her back again by slaying the demon. In the forest the sages ask Rama for his protection, and he promises to deliver them from the oppression of the Titans. Sita implores her husband, however, not to attack the Titans, for there are three failings born of desire: uttering falsehood, associating with another’s wife, and committing violence without provocation, the last of which is now showing itself in Rama. Sita pleads that the bearing of arms alters one’s mind the way fire changes a piece of wood. She asks Rama to renounce all thought of slaying the Titans, pointing out that the practice of war and asceticism in the forest are opposed to each other. She begs him to honor the moral code as it relates to peace.

Rama replies that the sages are unable to enjoy a peaceful life in the forest because of the Titans, and he has promised to aid them if they ask for his help. A female demon Shurpanakha tries to seduce Rama and Lakshmana; but when she attacks Sita, Lakshmana cuts off her ears and nose. Shurpanakha complains to her brother Khara, and he sends demons who are slain by Rama. Then Khara leads his army of demons against Rama. Rama destroys them and kills Khara.

Ravana, king of the demons, hears of their defeat and is persuaded by Shurpanakha to try to kill Rama so that he can wed Sita. The demon Maricha tries to dissuade Ravana, warning him against the sin of interfering with someone’s wife. However, Maricha assumes the form of a fawn and is slain by Rama. Hearing his cry, Sita insists that Lakshmana go to assist him even though it is his duty to guard Sita. In a rare lapse of character in her excessive love for Rama, Sita accuses Lakshmana of caring more for her than his own brother. With Lakshmana out of the way, Ravana approaches Sita, who defies him. Nevertheless he abducts her by force and takes her to the island of Lanka. Ravana tries to make Sita his consort, but she refuses and is given to Titan women to be guarded.

In vain Rama and Lakshmana search for Sita, and Rama’s sorrow turns to wrath. Eventually Rama is told what happened and where he can find Ravana. The fourth through the sixth books narrate the war against Ravana and the Titans by Rama and his allies in southern India who are referred to as monkeys. Their king Sugriva sends the powerful Hanuman to aid Rama. The monkeys search everywhere for Sita, and only after they refuse to eat does someone tell them where she is hidden. The monkeys are discouraged when they see the ocean, but Hanuman is able to fly over to Lanka and explore the enemy’s territory.

Once again Ravana tries to woo Sita, but she refuses again and prophesies the destruction of the Titans. Hanuman finds Sita, but she refuses to be rescued by him, though she gives him her jewel to take to Rama. Hanuman does considerable damage but is captured by the Titans. The Titan Bibishana pleads for Hanuman’s life out of respect for messengers. Hanuman escapes and sets fire to Lanka, then returns and urges the monkeys to rescue Sita.

Bibishana advises Ravana to send back Sita to avoid the war, warning that being in the wrong they are sure to be defeated by Rama. Ravana calls a council of war and is supported by flattering speeches. Bibishana is rebuffed by his brother Ravana and departs to the monkeys, who doubt his loyalty; but Rama accepts him as an ally, saying, “I shall never refuse to receive one who presents himself as a friend.”1 Bibishana tells them of the strength and extent of Ravana’s army.

The army of monkeys and Rama cross the sea to Lanka. Once again Ravana is advised, this time by his grandfather the Titan Malyavan, to return Sita and make peace with Rama. Again Ravana closes his ears to this speech, relying on his power to overcome the exiled Rama. In the battle Rama and Lakshmana are struck down by Ravana’s son, Indrajita, but they are revived by Garuda. Rama then defeats Ravana in battle but does not kill him. Ravana’s brother Kumbhakarna is able to turn the monkeys back, but he is slain by Rama.

Using invisibility Indrajita puts the monkey army out of action. Hanuman gets herbs from the Lord of the Mountains to heal the wounds of Rama and Lakshmana, and Lanka is set on fire again by the monkeys. Indrajita devises the stratagem of killing an apparition, which seemed to be Sita. When Rama hears the news that Sita has been slain, he falls to the ground like a tree whose roots have been severed. Lakshmana then delivers a despairing speech that virtue must not have its reward if such things could happen to the noble Rama. Bibishana, explaining that he is fighting against his brother because of the wrongs he has committed, helps Lakshmana to kill Indrajita.

Finally Rama and Ravana fight with magic weapons. Ravana flees; but later they fight again, and Ravana is killed. After the funeral and mourning for Ravana, Bimbishana is installed as king of Lanka. Hanuman carries the news to Sita, who pleads for mercy toward her former captors now captured themselves. Sita quotes an ancient saying,

Rama sends for Sita; but when they meet, he repudiates her because of suspicions based on her having lived in the house of another. He cannot believe that Ravana would not have enjoyed her ravishing beauty; so he tells her she may go where she pleases. Hearing this harsh speech from Rama, Sita weeps bitterly. Sita laments that she was always faithful to her husband in whatever was under her control. She accuses Rama of being worthless and to prove her innocence enters the flames of the sacrificial fire. Then Brahma reprimands Rama for acting like a man when he is really a god. After this divine speech Sita is restored from the extinguished pyre and given back to Rama by the fire god Agni, who declares her innocent. This ordeal by fire had to occur though, so that other people would know Sita’s innocence.

Rama and Sita return to Ayodhya, where Rama is installed as king. In the later epilog (seventh book) a dark cloud still hangs over Sita, and people criticize Rama for taking her back. So she goes once more to live in the forest and is taken in by Valmiki, the author of the epic. Sita gives birth to twins, who are taught to recite the poem. Rama recognizes his sons as minstrels and asks Valmiki to return his wife; but unable to remove the people’s suspicions, her heart broken, she asks the Earth to take her back, and her end mirrors her beginning. Finally death seeks out Rama, and he ascends to heaven.

This story which justifies the conquest of southern India and the island of Lanka nevertheless acknowledges the virtue of the dark-skinned southern peoples, who though referred to as monkeys are nonetheless on the side of good. The military hero Rama is divinized and becomes an object of worship as an incarnation of the Preserver Vishnu, and Sita is held up as the model of outstanding womanhood exemplifying beauty, patience, loyalty, kindness, and mercy.

The legendary author of the Mahabharata is Vyasa, who is also given credit for compiling the Vedas and writing the Puranas. The 24,000 couplets of the Bharata were gradually expanded to become over 100,000 making the Mahabharata the longest poem in the world and probably the work of many hands. Vyasa managed to portray himself in the poem as the progenitor of the two kings whose sons fight for the kingdom of Bharata, as his mother asks him to father sons on a widow and the wife of the celibate Bhishma and a third on a low-caste servant maid. Dhritarashtra is born blind because his mother closed her eyes, and Pandu is pale because his mother Ambika was pale with fear. Ironically the third who is of low caste, Vidura, turns out to be the wisest, resembling the god Dharma (justice, virtue) even more than Yudhishthira, who is the son of Dharma.

Because of Dhritarashtra’s blindness, Pandu was made king. One day while hunting Pandu shot a deer that was coupling with its mate and was cursed with the fate that if he ever mated with his wife he would also die. So Pandu was celibate and practiced austerity in the forest along with his wives Kunti and Madri after they gave away their royal wealth to charity. Pandu asked Kunti to give him sons from a man equal or superior to him. Kunti had been given a mantra by which she could summon any god she desired to father children. She had already given birth to Karna, whose father was the sun; she had put him in a basket, and he not knowing his parents was raised by a charioteer. Then through Kunti Dharma (Justice) became the father of Yudhishthira, Vayu (Wind) the father of Bhima, and the powerful Indra father of Arjuna. She told the mantra to Madri, who gave birth to Nakula and Sahadeva, twin sons of the Ashvins. However, Pandu made love to Madri and died, joined on his funeral pyre by Madri. Kunti raised the five Pandava sons, while the blind Dhritarashtra ruled the kingdom. Meanwhile the latter’s wife gave birth to a hundred sons with Duryodhana the oldest. Vidura prophesied that Duryodhana would bring about destruction, but his warnings were ignored.

Duryodhana tried to kill Bhima but failed. Bhishma arranged for the Brahmin Drona to teach all the princes. Arjuna excelled in the martial arts and was given special attention by Drona. Karna was also a great warrior and became a friend and supporter of Duryodhana. For Drona’s tutorial fee Karna, Duryodhana and his brothers captured King Drupada. Dhritarashtra declared the oldest and most honest Yudhishthira heir to his throne. So Duryodhana and his brothers planned to burn to death Kunti and her five sons, but the Pandavas discovered the plot and escaped through underground tunnels from the burning house.

Arjuna won a beautiful bride in Draupadi, but when he told his mother he had a gift for her, she said that he must share it with all his brothers. Since the mother’s word could not be broken, all five brothers married Draupadi, a practice forbidden by the Vedas. Both Bhishma and Drona advised Dhritarashtra to give the Pandavas a share in the kingdom with his own sons. The Pandavas were given the city of Indraprastha from whence they could rule their half of the kingdom. Accidentally breaking in on his brother Yudhishthira with their wife, Arjuna had to go into exile for twelve years and practice chastity (brahmacharya). But the maiden Ulupi persuaded Arjuna that his celibacy only related to his wife Draupadi, and he eventually married Krishna’s sister Subhadra, who gave birth to their son Abhimanyu. Draupadi also had a son by each of her five husbands, while Arjuna’s efforts gained him divine weapons from Indra.

Krishna, who later was made into a god, urged Yudhisthira and his brothers to attack Jarasandha, who had captured some kings. Bhima defeated Jarasandha in single combat, and Krishna released the imprisoned kings. Then Yudhishthira sent his four brothers in the four directions to conquer India. Krishna is criticized by Sishupala for killing women and cattle, but Krishna slices off Sishupala’s head with a discus.

To win the Pandavas’ territory Duryodhana invites Yudhishthira to the palace to play dice with the skilled dice-cheater Shakuni. Yudhishthira’s weakness for gambling causes him to lose everything he owns and even his four brothers, himself, and finally their wife. When Draupadi is summoned, she is in retreat because of her monthly period. She is dressed only in a single blood-stained garment, but she is dragged by the hair into the hall by Dushasana. Draupadi questions what right her husband had to stake her when he had already lost his own freedom. Nonetheless she is insulted by Duryodhana and his brothers, who try to disrobe her; a miracle is performed by Krishna so that the cloth pulled from her body never ends. (In the past Draupadi had bandaged the wounded Krishna.) Spared this ultimate humiliation, Draupadi is given three boons by King Dhritarashtra and asks only for the return of Yudhishthira and his four brothers. Finally they decide to play one more dice game for the kingdom, the loser of which will have to go into exile for twelve years and be in hiding without being discovered for one year after that. Once again Yudhishthira loses, and the Pandavas depart for the forest. Vidura pleads with his brother to allow the Pandava sons to return or else ruin will result, but once again he is ignored.

In the forest Yudhishthira learns the value of forgiveness. Draupadi is a model and devoted wife to the brothers. Of the many stories there is one in which each of the brothers drinks water and dies at a river before answering a question, but Yudhishthira wisely answers all the questions and brings his brothers back to life. Nonviolence is considered the highest duty.

During the thirteenth year they take on disguises and live in Virata’s kingdom. A general tries to molest Draupadi, but he is killed by Bhima. After this dangerous year is completed, Krishna is sent as an envoy to ask for the Pandavas’ half of the kingdom. When this is refused, everyone prepares for the great war. Krishna offers one side his army and the other himself though he will not fight. His army fights with Duryodhana, and Krishna becomes the charioteer for Arjuna.

As the war is about to start, Arjuna refuses to fight his cousins; but in the Bhagavad-Gita Krishna encourages him to fight as a warrior and teaches him about yoga and non-attachment to the fruits of action. Arjuna then decides to fight, and Yudhishthira approaches both Bhishma and Drona, asking for their blessings, although they are on the opposite side. After eight days of battles Yudhishthira also wants to stop fighting and retire to the forest; but Krishna tells him to ask Bhishma how he can be killed, because Bhishma has control over his own death. Shikhandin, reincarnation of the woman Amba, who had been rejected by Bhishma and swore to kill him, is able to attack Bhishma because he will not fight a woman. Tired of all the killing Bhishma wants to die, and he is mortally wounded by Arjuna’s arrows.

Drona is given command of Duryodhana’s armies. He is practically invincible, but he is discouraged by the lie that his son is dead. Yudhishthira, who is known for his truthfulness, says that Ashvatthaman is dead after Bhima kills an elephant with that name, but the intent is clearly to mislead Drona. Drona lays down his weapons, and his head is cut off by Dhrishtadyumna. In a family quarrel Arjuna is on the verge of killing Yudhishthira, but Krishna intervenes and says that nonviolence (ahimsa) is even more important that truthfulness. Truth is the highest virtue; but when life is in danger, even lying is permitted. Karna has sworn to kill Arjuna, but he is killed by Arjuna after his chariot gets stuck in the mud. The rules of fair fighting are increasingly being ignored.

On the eighteenth day of the war Duryodhana is wounded in the legs by Bhima even though this was also a violation of the rules they agreed on before the war. Krishna responds to Duryodhana’s taunts by reminding him that the dice game was crooked, how Draupadi had been insulted, and how Arjuna’s son Abhimanyu had been killed. All of Gandhari’s sons have been killed, but the five Pandavas have miraculously survived a war that was supposed to have had millions of warriors involved. In revenge Ashvatthaman violates another rule of war by attacking the Pandava camp at night and kills all of Draupadi’s sons. In anger Arjuna readies the weapons that could destroy the three worlds of heaven, earth, and hell, but the sages Narada and Vyasa appear to dissuade him from this use of omnicidal weapons.

Most of the rest of the poem after the great war is probably stories and ideas added later. Vidura explains that the story of the man enjoying a few drops of honey while in a well caught between a carnivore and a monstrous snake, hanging by a vine eaten away by rats is told by the knowers of liberation to suggest serenity in the midst of troubles.

The long twelfth book called Peace (Shanti) has been discussed in relation to Samkhya philosophy. Bhishma, before he dies, gives his teachings. Ironically the nine duties common to the four castes seem to have been much violated by the characters in this poem; they are: controlling anger, truthfulness, justice, forgiveness, having lawful children, purity, avoidance of quarrels, simplicity, and looking after dependents. According to Bhishma the duty of the warrior (Kshatriya) is to protect the people. Truth is the highest duty but must not be spoken if the truth actually covers a lie. From desire comes greed and wrong-doing, wrath, and lust, producing confusion, deception, egoism, showing-off, malice, revenge, shamelessness, pride, mistrust, adultery, lies, gluttony, and violence.

Vidura believes that justice (dharma) is more important than profit (artha) or pleasure (kama) ; but Krishna argues that profit is first, because action is what matters in the world. However, Yudhishthira chooses liberation (moksha) as best. Bhishma says that nothing sees like knowledge; nothing purifies like truth; nothing delights like giving; and nothing enslaves like desire. By being poor one has no enemies, but the rich are in the jaws of death; he chose poverty because it had more virtues. Giving up a little brings happiness, while giving up a lot brings supreme peace. Before Bhishma dies, the preceptor of the gods, Brihaspati, appears and explains that compassion is most virtuous, because such a person looks at everyone as if they were one’s own self. He teaches them the golden rule that one should never do to another what one would not want another to do to you; for when you hurt others, they turn and hurt you; but when you love others, they turn and love you. Brihaspati ascends to heaven, and Bhishma realizes that ahimsa (not hurting) is the highest religion, discipline, penance, sacrifice, happiness, truth, and merit.

Yudhishthira performs the kingly horse sacrifice and rules over a wide realm his family has subdued before he passes on the kingdom to Arjuna’s grandson Parikshit and retires with his brothers to seek heaven. On their divine ascent each of the brothers dies because of their shortcomings, but Yudhishthira will not leave behind his faithful dog, who is allowed into heaven with him as a symbol of dharma. Yudhishthira is thus able to enter heaven alive where he finds Duryodhana. Narada explains that there are no enmities in heaven, but Yudhishthira asks to see his brothers. He is led to a stinky unpleasant place, but he prefers to be in hell with his brothers. This too is a test, and he is reunited with Draupadi, who was an incarnation of Lakshmi, goddess of prosperity. The author concludes that profit and pleasure come from virtue. Pleasure and pain are not eternal; only the soul is eternal.

This poetic story of a great war that probably took place in the late tenth century BC is filled with stories and situations that describe the culture of ancient India and has been an entertaining schoolbook for millions. Along with the virtues it also reveals the vices of the conquering and warlike Aryans and their racist caste system. Even the divine Krishna becomes a spokesperson for the warrior mentality, as a nearly apocalyptic disaster destroys millions and threatens their whole world. Still a heroic epic of military glory like the Ramayana, the Mahabharata contains much more real and well defined characters and portrays many aspects of life. If only humanity could learn from its negative lessons of violence and ambition, perhaps the peace of the sages could be found.

The BHAGAVAD-GEETA is a section of the great Hindu epic, MAHABHARATA, probably the longest poem in all of literature. The GITA was written between the fifth century BC and the second century CE and is attributed to Vyasa. According to Aurobindo, who studied Vyasa’s writings, nothing disproves his authorship.

The MAHABHARATA tells the story of a civil war in ancient India between the sons of Kuru (Kauruvas) and the sons of Pandu (Pandavas) over a kingdom the Pandavas believe was stolen from them by the cheating of the Kauruvas. Every attempt by the Pandava brothers to regain their kingdom without war has failed.

The BHAGAVAD-GITA is primarily a dialog between Arjuna, the third Pandava brother, and his charioteer, Krishna. Remaining neutral, Krishna allowed one side to use his vassals in battle, while the other side could have him as a charioteer although he would not fight himself. The old blind King Dhritarashtra declined a great sage’s offer to give him sight for the battle, because he did not want to see the bloodshed. Instead the great sage gave Sanjaya the ability to perceive at a distance everything that was going on, and he describes the events for the King.

In the GITA Krishna, who is the uncle and friend of the Pandavas, gives Arjuna teachings on yoga, which means union and implies union with God. Krishna is considered by Hindus to be an incarnation of the god Vishnu, the preserver.

In the first chapter of the GITA, some of the heroes of the two armies are mentioned by King Duryodhana, the oldest Kaurava brother, first the Pandavas: the son of Drupada, Bhima, Arjuna, Yuyudhana, Virata, Drupada, Dhrishtaketu, Chekitana, the King of Kashi, Purujit, Kuntibhoja, Shaibya, Yudhamanyu, Uttamauja, the son of Subhadra, and the sons of Draupadi; then the Kauravas: Bhishma, Karna, Kripa, Ashvatthaman, Vikarna, Saumadatti, and Drona. When they blow their conch-horns, Arjuna’s brothers are named: Bhima, Yudhishthira, Nakula, and Sahadeva.

Throughout the text various epithets or nicknames are used for Krishna and Arjuna. Krishna is called: Madhava (descendant of Madhu), Hrishikesha (bristling-haired), Keshava (handsome-haired), Govinda (chief of herdsmen), slayer of Madhu (a demon), Janardana (agitator of humans), Varshneya (clansman of the Vrishnis), Vasudeva (son of Vasudeva), Hari, and slayer of Keshin (a demon). Arjuna is called: son of Pandu, Gudakesha (thick-haired), Partha (son of Pritha, Kunti’s original name), Kaunteya (son of Kunti), Bharata (ancient name of India, used for other characters as well), Bharata bull, wealth winner, foe scorcher, great-armed one, blameless one, tiger spirit, and Kuru’s joy or best of Kurus (Kuru being a common ancestor of both the Pandavas and the Kauravas). Gandiva is the name of Arjuna’s bow.

- Rig Veda

- Yajur Veda

- Sama Veda

- Atharva Veda

The Srutis are called the Vedas, or the Amnaya. The Hindus have received their religion through revelation, the Vedas. These are direct intuitional revelations and are held to be Apaurusheya or entirely superhuman, without any author in particular. The Veda is the glorious pride of the Hindus, nay, of the whole world!

The term Veda comes from the root ‘Vid’, to know. The word Veda means knowledge. When it is applied to scripture, it signifies a book of knowledge. The Vedas are the foundational scriptures of the Hindus. The Veda is the source of the other five sets of scriptures, why, even of the secular and the materialistic. The Veda is the storehouse of Indian wisdom and is a memorable glory which man can never forget till eternity.

The Vedas are the eternal truths revealed by God to the great ancient Rishis of India. The word Rishi means a Seer, from dris, to see. He is the Mantra-Drashta, seer of Mantra or thought. The thought was not his own. The Rishis saw the truths or heard them. Therefore, the Vedas are what are heard (Sruti). The Rishi did not write. He did not create it out of his mind. He was the seer of thought which existed already. He was only the spiritual discoverer of the thought. He is not the inventor of the Veda.

THE UNIQUE GLORY OF THE VEDAS

The Vedas represent the spiritual experiences of the Rishis of yore. The Rishi is only a medium or an agent to transmit to people the intuitional experiences which he received. The truths of the Vedas are revelations. All the other religions of the world claim their authority as being delivered by special messengers of God to certain persons, but the Vedas do not owe their authority to any one. They are themselves the authority as they are eternal, as they are the Knowledge of the Lord.

Lord Brahma, the Creator, imparted the divine knowledge to the Rishis or Seers. The Rishis disseminated the knowledge. The Vedic Rishis were great realised persons who had direct intuitive perception of Brahman or the Truth. They were inspired writers. They built a simple, grand and perfect system of religion and philosophy from which the founders and teachers of all other religions have drawn their inspiration.

The Vedas are the oldest books in the library of man. The truths contained in all religions are derived from the Vedas and are ultimately traceable to the Vedas. The Vedas are the fountain-head of religion. The Vedas are the ultimate source to which all religious knowledge can be traced. Religion is of divine origin. It was revealed by God to man in the earliest times. It is embodied in the Vedas.

The Vedas are eternal. They are without beginning and end. An ignorant man, may say how a book can be without beginning or end. By the Vedas, no books are meant. Vedas came out of the breath of the Lord. They are not the composition of any human mind. They were never written, never created. They are eternal and impersonal. The date of the Vedas has never been fixed. It can never be fixed. Vedas are eternal spiritual truths. Vedas are an embodiment of divine knowledge. The books may be destroyed, but the knowledge cannot be destroyed. Knowledge is eternal. In that sense, the Vedas are eternal.

DIVISIONS OF THE VEDAS

The Veda is divided into four great books: the Rig-Veda, the Yajur-Veda, the Sama-Veda and the Atharva-Veda. The Yajur-Veda is again divided into two parts, the Sukla and the Krishna. The Krishna or the Taittiriya is the older book and the Sukla or the Vajasaneya is a later revelation to sage Yajnavalkya from the resplendent Sun-God.

The Rig-Veda is divided into twenty-one sections, the Yajur-Veda into one hundred and nine sections, the Sama-Veda into one thousand sections and the Atharva-Veda into fifty sections. In all, the whole Veda is thus divided into one thousand one hundred and eighty recensions.

Each Veda consists of four parts: the Mantra-Samhitas or hymns, the Brahmanas or explanations of Mantras or rituals, the Aranyakas, and the Upanishads. The division of the Vedas into four parts is to suit the four stages in a man’s life.

The Mantra-Samhitas are hymns in praise of the Vedic God for attaining material prosperity here and happiness hereafter. They are metrical poems comprising prayers, hymns and incantations addressed to various deities, both subjective and objective. The Mantra portion of the Vedas is useful for the Brahmacharins.

The Rig-Veda Samhita is the grandest book of the Hindus, the oldest and the best. It is the Great Indian Bible, which no Hindu would forget to adore from the core of his heart. Its style, the language and the tone are most beautiful and mysterious. Its immortal Mantras embody the greatest truths of existence, and it is perhaps the greatest treasure in all the scriptural literature of the world. Its priest is called the Hotri.

The Yajur-Veda Samhita is mostly in prose and is meant to be used by the Adhvaryu, the Yajur-Vedic priest, for superfluous explanations of the rites in sacrifices, supplementing the Rig-Vedic Mantras.

The Sama-Veda Samhita is mostly borrowed from the Rig-Vedic Samhita, and is meant to be sung by the Udgatri, the Sama Vedic priest, in sacrifices.

The Atharva-Veda Samhita is meant to be used by the Brahma, the Atharva-Vedic priest, to correct the mispronunciations and wrong performances that may accidentally be committed by the other three priests of the sacrifice.

The Brahmana portions guide people to perform sacrificial rites. They are prose explanations of the method of using the Mantras in the Yajna or the sacrifice. The Brahmana portion is suitable for the householders.

There are two Brahmanas to the Rig-Veda-the Aitareya and the Sankhayana. “The Rig-Veda”, says Max Muller, “is the most ancient book of the world. The sacred hymns of the Brahmanas stand unparalleled in the literature of the whole world; and their preservation might well be called miraculous.”

The Satapatha Brahmana belongs to the Sukla-Yajur-Veda. The Krishna-Yajur-Veda has the Taittiriya and the Maitrayana Brahmanas. The Tandya or Panchavimsa, the Shadvimsa, the Chhandogya, the Adbhuta, the Arsheya and the Upanishad Brahmanas belong to the Sama-Veda. The Brahmana of the Atharva-Veda is called the Gopatha. Each of the Brahmanas has got an Aranyaka.

The Aranyakas are the forest books, the mystical sylvan texts which give philosophical interpretations of the rituals. The Aranyakas are intended for the Vanaprasthas or hermits who prepare themselves for taking Sannyasa.

The Upanishads are the most important portion of the Vedas. The Upanishads contain the essence or the knowledge portion of the Vedas. The philosophy of the Upanishads is sublime, profound, lofty and soul-stirring. The Upanishads speak of the identity of the individual soul and the Supreme Soul. They reveal the most subtle and deep spiritual truths. The Upanishads are useful for the Sannyasins.

The subject matter of the whole Veda is divided into Karma- Kanda, Upasana-Kanda and Jnana-Kanda. The Karma-Kanda or Ritualistic Section deals with various sacrifices and rituals. The Upasana-Kanda or Worship-Section deals with various kinds of worship or meditation. The Jnana-Kanda or Knowledge-Section deals with the highest knowledge of Nirguna Brahman. The Mantras and the Brahmanas constitute Karma-Kanda; the Aranyakas Upasana-Kanda; and the Upanishads Jnana-Kanda.

THE ESSENCE OF THE VEDAS

Live in the spirit of the teachings of the Vedas. Learn to discriminate between the permanent and the impermanent. Behold the Self in all beings, in all objects. Names and forms are illusory. Therefore sublate them. Feel that there is nothing but the Self. Share what you have,-physical, mental, moral or spiritual,-with all. Serve the Self in all. Feel when you serve others, that you are serving your own Self. Love thy neighbour as thyself. Melt all illusory differences. Remove all barriers that separate man from man. Mix with all. Embrace all. Destroy the sex-idea and body-idea by constantly thinking of the Self or the sexless, bodiless Atman. Fix the mind on the Self when you work. This is the essence of the teachings of the Vedas and sages of yore. This is real, eternal life in Atman. Put these things in practice in the daily battle of life. You will shine as a dynamic Yogi or a Jivanmukta. There is no doubt of this.

- Kenopanishad

- Kathopanishad

- Aitereyopanishad

- Brihadaranyakopanishad

- Chandogyopanishad

- Isavasyopanishad

- Mandukyopanishad

- Mundakopanishad

- Prashnopanishad

- Swetashtaropanishad

- Taitareyopanishad

Upanishad means the inner or mystic teaching. The term Upanishad is derived from upa (near), ni (down) and s(h)ad (to sit), i.e., sitting down near. Groups of pupils sit near the teacher to learn from him the secret doctrine. In the quietude of the forest hermitages the Upanishad thinkers pondered on the problems of deepest concerns and communicated their knowledge to fit pupils near them. Samkara derives the word Upanishad as a substitute from the root sad, ‘to loosen.,’ ‘to reach’ or ‘to destroy’ with Upa and ni as prefixes and kvip as termination. If this determination is accepted, upanishad means brahma-knowledge by which ignorance is loosened or destroyed. The treatises that deal with brahma-knowledge are called the Upanishads and so pass for the Vedanta. The different derivations together make out that the Upanishads give us both spiritual vision and philosophical argument. There is a core of certainty which is essentially incommunicable except by a way of life. It is by a strictly personal effort that one can reach the truth.

The Upanishads more clearly set forth the prime Vedic doctrines like Self-realization, yoga and meditation, karma and reincarnation, which were hidden or kept veiled under the symbols of the older mystery religion. The older Upanishads are usually affixed to a particularly Veda, through a Brahmana or Aranyaka. The more recent ones are not. The Upanishads became prevalent some centuries before the time of Krishna and Buddha.

The main figure in the Upanishads, though not present in many of them, is the sage Yajnavalkya. Most of the great teachings of later Hindu and Buddhist philosophy derive from him. He taught the great doctrine of “neti-neti”, the view that truth can be found only through the negation of all thoughts about it. Other important Upanishadic sages are Uddalaka Aruni, Shwetaketu, Shandilya, Aitareya, Pippalada, Sanat Kumara. Many earlier Vedic teachers like Manu, Brihaspati, Ayasya and Narada are also found in the Upanishads.

In the Upanishads the spiritual meanings of the Vedic texts are brought out and emphasized in their own right.

The Puranas are of the same class as the Itihasas (the Ramayana, Mahabharata, etc.). They have five characteristics (Pancha Lakshana), viz., history, cosmology (with various symbolical illustrations of philosophical principles), secondary creation, genealogy of kings, and of Manvantaras (the period of Manu’s rule consisting of 71 celestial Yugas or 308,448,000 years). All the Puranas belong to the class of Suhrit-Sammitas, or the Friendly Treatises, while the Vedas are called the Prabhu-Sammitas or the Commanding Treatises with great authority.

Vyasa is the compiler of the Puranas from age to age; and for this age, he is Krishna-Dvaipayana, the son of Parasara.

The Puranas were written to popularise the religion of the Vedas. They contain the essence of the Vedas. The aim of the Puranas is to impress on the minds of the masses the teachings of the Vedas and to generate in them devotion to God, through concrete examples, myths, stories, legends, lives of saints, kings and great men, allegories and chronicles of great historical events. The sages made use of these things to illustrate the eternal principles of religion. The Puranas were meant, not for the scholars, but for the ordinary people who could not understand high philosophy and who could not study the Vedas.

The Darsanas or schools of philosophy are very stiff. They are meant only for the learned few. The Puranas are meant for the masses with inferior intellect. Religion is taught in a very easy and interesting way through the Puranas. Even to this day, the Puranas are popular. The Puranas contain the history of remote times. They also give a description of the regions of the universe not visible to the ordinary physical eye. They are very interesting to read and are full of information of all kinds. Children hear the stories from their grandmothers. Pundits and Purohits hold Kathas or religious discourses in temples, on banks of rivers and in other important places. Agriculturists, labourers and bazaar people hear the stories.

Eighteen Puranas

There are eighteen main Puranas and an equal number of subsidiary Puranas or Upa-Puranas. The main Puranas are: Vishnu Purana, Naradiya Purana, Srimad Bhagavata Purana, Garuda (Suparna) Purana, Padma Purana, Varaha Purana, Brahma Purana, Brahmanda Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Markandeya Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Vamana Purana, Matsya Purana, Kurma Purana, Linga Purana, Siva Purana, Skanda Purana and Agni Purana. Of these, six are Sattvic Puranas and glorify Vishnu; six are Rajasic and glorify Brahma; six are Tamasic and they glorify Siva.

Neophytes or beginners in the spiritual path are puzzled when they go through Siva Purana and Vishnu Purana. In Siva Purana, Lord Siva is highly eulogised and an inferior position is given to Lord Vishnu. Sometimes Vishnu is belittled. In Vishnu Purana, Lord Hari is highly eulogised and an inferior status is given to Lord Siva. Sometimes Lord Siva is belittled. This is only to increase the faith of the devotees in their particular Ishta-Devata. Lord Siva and Lord Vishnu are one.

The best among the Puranas are the Srimad Bhagavata and the Vishnu Purana. The most popular is the Srimad Bhagavata Purana. Next comes Vishnu Purana. A portion of the Markandeya Purana is well known to all Hindus as Chandi, or Devimahatmya. Worship of God as the Divine Mother is its theme. Chandi is read widely by the Hindus on sacred days and Navaratri (Durga Puja) days.

Ten Avataras And Their Purpose

The Srimad Bhagavata Purana is a chronicle of the various Avataras of Lord Vishnu. There are ten Avataras of Vishnu. The aim of every Avatara is to save the world from some great danger, to destroy the wicked and protect the virtuous. The ten Avataras are: Matsya (The Fish), Kurma (The Tortoise), Varaha (The Boar), Narasimha (The Man-Lion), Vamana (The Dwarf), Parasurama (Rama with the axe, the destroyer of the Kshatriya race), Ramachandra (the hero of the Ramayana—the son of Dasaratha, who destroyed Ravana), Sri Krishna, the teacher of the Gita, Buddha (the prince-ascetic, founder of Buddhism), and Kalki (the hero riding on a white horse, who is to come at the end of the Kali-Yuga).

The object of the Matsya Avatara was to save Vaivasvata Manu from destruction by a deluge. The object of Kurma Avatara was to enable the world to recover some precious things which were lost in the deluge. The Kurma gave its back for keeping the churning rod when the Gods and the Asuras churned the ocean of milk. The purpose of Varaha Avatara was to rescue, from the waters, the earth which had been dragged down by a demon named Hiranyaksha. The purpose of Narasimha Avatara, half-lion and half-man, was to free the world from the oppression of Hiranyakasipu, a demon, the father of Bhakta Prahlada. The object of Vamana Avatara was to restore the power of the gods which had been eclipsed by the penance and devotion of King Bali. The object of Parasurama Avatara was to deliver the country from the oppression of the Kshatriya rulers. Parasurama destroyed the Kshatriya race twenty-one times. The object of Rama Avatara was to destroy the wicked Ravana. The object of Sri Krishna Avatara was to destroy Kamsa and other demons, to deliver His wonderful message of the Gita in the Mahabharata war, and to become the centre of the Bhakti schools of India. The object of Buddha Avatara was to prohibit animal sacrifices and teach piety. The object of the Kalki Avatara is the destruction of the wicked and the re-establishment of virtue.

Lilas of Lord Siva

Lord Siva incarnated himself in the form of Dakshinamurti to impart knowledge to the four Kumaras. He took human form to initiate Sambandhar, Manikkavasagar, Pattinathar. He appeared in flesh and blood to help his devotees and relieve their sufferings. The divine Lilas or sports of Lord Siva are recorded in the Tamil Puranas like Siva Purana, Periya Purana, Siva Parakramam and Tiruvilayadal Purana.

The eighteen Upa-Puranas are: Sanatkumara, Narasimha, Brihannaradiya, Sivarahasya, Durvasa, Kapila, Vamana, Bhargava, Varuna, Kalika, Samba, Nandi, Surya, Parasara, Vasishtha, Devi-Bhagavata, Ganesa and Hamsa.

Study of the Puranas, listening to sacred recitals of scriptures, describing and expounding of the transcendent Lilas of the Blessed Lord—these form an important part of Sadhana of the Lord’s devotees. It is most pleasing to the Lord. Sravana is a part of Navavidha-Bhakti. Kathas and Upanyasas open the springs of devotion in the hearts of hearers and develop Prema-Bhakti which confers immortality on the Jiva.

The language of the Vedas is archaic, and the subtle philosophy of Vedanta and the Upanishads is extremely difficult to grasp and assimilate. Hence, the Puranas are of special value as they present philosophical truths and precious teachings in an easier manner. They give ready access to the mysteries of life and the key to bliss. Imbibe their teachings. Start a new life of Dharma-Nishtha and Adhyatmic Sadhana from this very day, and attain Immortality.

- Vedic Education

- Nirukta

- Chanda Shastra

- Astrology

- Kalpa

- Sanskrit Grammer

Shastras are a part of the Smriti (“remembered”) literature. Dharma Sutras, or manuals on dharma, contain rules of conduct and rites as they were practiced in a number of branches of the Vedic schools.

Their principal contents address the duties of people at various stages of life or ashramas (studenthood, householdership, retirement, and asceticism); dietary regulations; offenses and expiations; and the rights and duties of kings. They discuss purification rites, funerary ceremonies, forms of hospitality, and daily oblations besides juridical matters. The more important of these texts are the sutras of Gautama, Baudhayana, and Apastamba. The contents of these works were further elaborated in Dharma Shastras, which in turn became the basis of Hindu law.

First among them stands the Dharma Shastra of Manu, also known as the Manu-smriti (“Tradition of Manu”; c. AD 200), with 2,694 stanzas divided into 12 chapters. It deals with various topics such as cosmogony, definition of dharma, the sacraments, initiation and Vedic study, the eight forms of marriage, hospitality and funerary rites, dietary laws, pollution and purification, rules for women and wives, royal law, eighteen categories of juridical matters, and finally more religious matters, including donations, rites of reparation, the doctrine of karma, the soul, and punishment in hell. Law in the juridical sense is thus completely embedded in religious law and practice.

The framework is provided by the model of the four-class society. The influence of the Dharma Shastra of Manu has been enormous on the Hindu society as it provided practical morality. Second only to Manu is the Dharma Shastra of Yajñavalkya; its 1,013 stanzas are distributed under the three headings of good conduct, law, and expiation.

- Kruta Yuga

- Treta Yuga

- Dwapara Yuga

- Kali Yuga

Prior to the creation of the universe. Lord Vishnu lies asleep on the ocean of all causes. He rests upon a serpent bed with thousands of cobra-like hoods. While asleep, a lotus sprouts from His navel. Upon this lotus is born Brahma the creator of the universe. Lord Brahma lives for a hundred years and then dies, while Lord Vishnu remains. One year of Brahma consists of three hundred and sixty days. At the beginning of each day Brahma creates the living beings that reside in the universe and at the end of each day the living beings are absorbed into Brahma while he sleeps on the lotus. On day of Brahma is known as a KALPA. Within each KALPA there are fourteen MANUS and within each MANU are seventy one CHATUR-YUGAS. Each CHATUR-YUGA is divided into four parts called YUGAPADAS.

From thee chapter of Surya-Siddhanta, the most revered authoritative source of Hindu astronomy, we have the following passage:

* That which begins with respirations (prana) is called real…….Six respirations make a vinadi, sixty of these a nadi:

* And sixty nadis make a sidereal day and night. Of thirty of these sidereal days is composed a month; a civil (savana) month consists of as many sunrises;

* A lunar month, of as many lunar days (tithi); a solar (saura) month is determined by the entrance of the Sun into a sign of the zodiac; twelvemonths make a year. This is called a day of the gods.

* The day and night of the gods and of the demons are mutually opposed to one another. Six times sixty of them are a year of the gods, and likewise to the demons.

* Twelve thousand of these divine years are denominated a chatur-yuga; of ten-thousand times four hundred and thirty two solar years is composed that chatur-yuga, with its dawn and twilight. The difference of the krita-yuga and the other yugas, as measured by the difference in the number of the feet of virtue in each is as follows:

* The tenth part of a chatur-yuga, multiplied successively by four, three, two, and one, gives the length of the krita and the other yugas: the sixth part of each belongs to its dawn and twilight.

* One and seventy chatur-yugas make a manu; at its end is a twilight which has the number of years of a krita-yuga, and which is a deluge.

* In a kalpa are reckoned fourteen manus with their respective twilights; at the commencement of the kalpa is a fifteenth dawn, having the length of a krita-yuga.

* The kalpa, thus composed of a thousand chatur-yugas, and which brings about the destruction of all that exists, is a day of Brahma; his night is of the same length.

* His extreme age is a hundred, according to this valuation of a day and a night. The half of his life is past; of the remainder, this is the firsts kalpa.

* And of this kalpa, six manus are past, with theirrespective twilights; and of the Manu son of Vivasvat, twenty seven chatur-yugas are past;

* Of the present, the twenty eighth chatur-yuga, this krita yuga is past……..

Now to make plain what is stated above. Commentaries are very clear on the fact that in verse 12 the “sidereal day” refers to a revolution of the Earth relative to any fixed star and is the true revolution reference point of the Earth. Verse 13 refers to “a day of the gods” means one sidereal year. A night of the gods is half a sidereal year. Verse 21 mentions “his extreme age is a hundred refers to the lifespan of Brahma and consists of one hundred years of 360 days. Each of these days being two kalpas long. Verse 23 shows that the Surya-Siddhanta was composed right after krita-yuga and during the treta-yuga. The present yuga we are in right now is the kali-yuga which is said to have begun on Friday February 18th 3102 B.C. of the Julian calendar. This becomes clearer when represented in a tabular form.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

INFRASTRUCTURE OF THE CHATUR-YUGA PERIOD

| PERIOD | DIVINE YEARS | SOLAR YEARS | PERIOD | DIVINE YEARS | SOLAR YEARS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dawn | 400 | 144,000 | Dawn | 300 | 108,000 |

| KRITA YUGA | 4000 | 1,440,000 | TRETA YUGA | 3,000 | 1,080,000 |

| twilight | 400 | 144,000 | twilight | 300 | 108,000 |

| TOTAL | 4,800 | 1,728,000 | TOTAL | 3,600 | 1,296,000 |

| PERIOD | DIVINE YEARS | SOLAR YEARS | PERIOD | DIVINE YEARS | SOLAR YEARS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dawn | 200 | 72,000 | Dawn | 100 | 36,000 |

| DVAPARA YUGA | 2000 | 720,000 | KALI YUGA | 1,000 | 360,000 |

| twilight | 200 | 72,000 | twilight | 100 | 36,000 |

| TOTAL | 2,400 | 864,000 | TOTAL | 1,200 | 432,000 |

| CHATUR YUGA TOTAL | 12,000 DIVINE YEARS | 4,320,000 SOLAR YEARS |